According to the Constitution, Portugal is a democratic state based on the rule of law, the sovereignty of people, the pluralism of democratic expression and respect for fundamental rights and freedoms for all citizens.

In the nineteen seventies Portugal underwent a series of major political, social and economic changes, alongside with the revolution that occurred in 1974, marking the end of the dictatorship and colonial regime. This event re-established the fundamental rights and liberties for all citizens, which are now documented in the constitution of the Portuguese Republic. During this period, music education was not a major concern of the political agenda. However, in that time, music became a way of expressing the novel ideas of a democratic country; young people saw many of their feelings and thoughts disclosed in this “political engaged music” (Mota, 2001, p.152), that slowly also became a part of many activities inside the music classroom.

After 1974, there was an emergence of pop/rock bands and musicians that composed their own songs without having any formal knowledge about music education. They composed and played by ear (as they do nowadays), incorporating in their songs styles and rhythms from Portugal's past African colonies. This has also had an impact in music education. As stated by Mota, “Some young teachers have begun incorporating this music and its powerful rhythms in their music classrooms which is a total new direction to the Portuguese music” (Mota, 2001, p.152, 153). Later these pop/rock bands were also influenced by U.K and American counter-parts and by the life style of diverse musicians living in these countries.

In the year of 1986 music education in Portugal underwent its first big reform. Inspired by the international emphasis on art education and by the visit of several music educators philosophically related to the ideas of Dalcroze, Orff or Willlems, the Portuguese music education community emphasised that pupils should, first of all, be involved in several musical practices. The focus was not anymore in music theory (that should be introduced later) but in the ways children could actively engage music. This was also the beginning of a period devoted to reflection about the goals, practices and values of music education in schools. Institutions such as APEM (Associação Portuguesa de Educação Musical), the Portuguese National Affiliate of ISME, or Gulbenkian, organised several seminars, conferences and workshops, spreading a new philosophy for music education and inviting innovative and inspiring music educators and musicians such as John Paynter or Murray Schaffer.

1986 was also the year in which Portugal became a member of the European Economic Community (EEC), now the European Union (EU), and, for a long period, has achieved several improvements in the economic and social spheres. However, in the recent past, and similarly to what happened in many other European countries, Portugal suffered from a major financial and economic crisis, which affected both individual, community, and institutional dimensions of Portuguese lives. This crisis also had a strong negative impact on the Portuguese education system. In what concerns music education and also as a consequence of the economic and financial crisis, many ambiguous and negative aspects emerged, concerning not only the place of music education in the Portuguese curriculum but also the role, status and professional development of music teachers.

Music Education in Public General Schools

In Portugal, compulsory education is divided into four learning cycles. As shown in Table 1, music education is a compulsory subject only in the first and second cycles of education.

|

|

Number of Academic Years |

Pupils’ Age |

Music Education as a Curriculum Subject |

Professional responsible for teaching music education |

|

1st Cycle

|

4 |

6-9 |

Compulsory |

Primary Teacher |

|

2nd Cycle |

4 |

10-11 |

Compulsory |

Specialist Music Teacher |

|

3rd Cycle |

3 |

12-14 |

Optional in the two first years of the cycle. Non-existent in the third. |

Specialist Music Teacher |

|

Secondary School |

3 |

15-18 |

Non-existent |

Non-existent |

Table 1: Music Education during basic education

Curricula - 1st Cycle

During the first cycle of education, music education is a compulsory subject of the curriculum, as part of a block of 5 hours of artistic education, and should be taught by primary teachers. However, there are many primary teachers who feel unconfident to teach music; they argue that that their teacher training does not give them sufficient preparation in what regards music teaching and learning.

In 2006, the Ministry of Education launched a programme that consisted of ‘10 weekly hours of extra-curricular activities (English, music, sports) taught by specialist teachers, that children attend on a voluntary basis’ (Boal-Palheiros & Encarnação, 2008, p. 98). A music syllabus was created with specific guidelines intended to help teachers to develop their work. The Portuguese Ministry of Education entitled these activities ‘Curriculum Enrichment Activities’ (Ministry of Education, 2006). Even though music education is part of the official curriculum, the implementation of the ‘curriculum enrichment activities’ has been the cause of some ambiguity as there is repetition of music in both curriculums. Mota (2007) outlined some concerns about the implementation of music as an enrichment activity, explaining that with the new programme, music education may be discarded from the elementary curriculum in some schools. Pupils not attending afterschool enrichment activities could be in danger of not receiving any music education. As a possible solution, (Mota 2007; Mota, Costa & Leite, 2002) advocated for a collaborative work between the primary teacher and a music specialist. This collaborative work could be done through the implementation of projects that, on the one hand, would have their focus on making music, through performance, composition or audition, and, on the other hand, would embrace a real interdisciplinary process relating music with other arts and also with other curriculum subjects. However, until now, this has not become general practice, and pupils receive music education in primary schools within the voluntary ‘curricular enrichment activities’, while provision of musical activities in school hours depends on the particular primary teacher.

Curricula – 2nd and 3rd Cycles

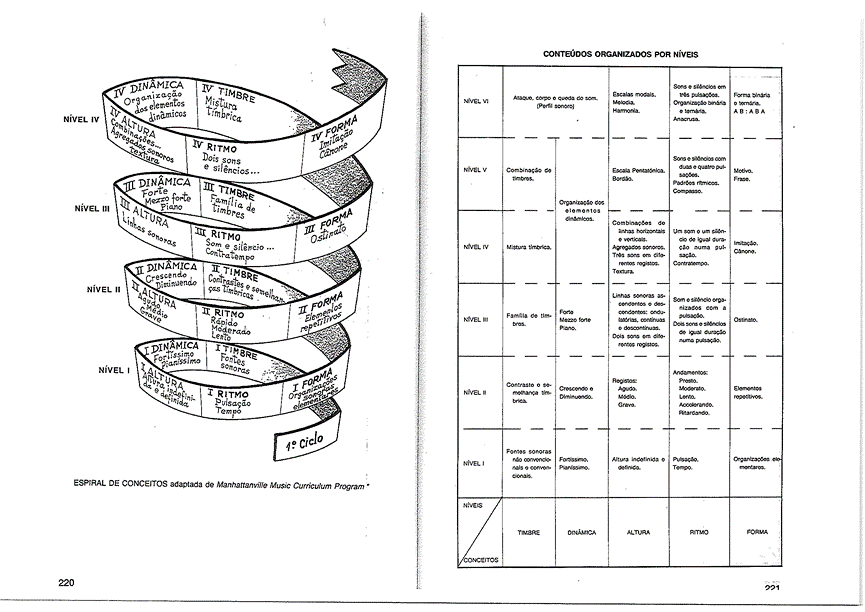

In Middle School the curriculum that prevails nowadays was inspired in the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (MMCP), organised through a spiral around five main concepts: timbre, dynamics, pitch, rhythm, form. This syllabus was created in 1989 by a scientific committee that worked on the basis of an epistemological ground that highlighted the conceptual development theorised by scholars such as Jerome Bruner (2009). It was the first time that Portugal had a music education program based on a logic of musical development and that offered a really innovative way to teach and learn music. This educational program intended to move away from some retrograde practices, to bring contemporary music into the classroom and to help students to achieve a conceptual understanding of music through exploration and experimentation. However, the Ministry of Education misunderstood the guidelines given by this committee, transforming what was a spiral in a closed grid (see fig. 1). Thus, many music teachers began using music to exemplify the meaning of concepts, or to “test” students regarding those concepts. It also led to an emphasis on music theory, rather than on making music.

In 2001, policy makers designed a curriculum model named “National Curriculum for Basic Education: Essential Competencies” (2001). The idea of this document was not to replace the other one, but to be the ground in which the concepts of the 1989 program were approached. In terms of music education, this new document consisted in a series of musical competences, highlighting music as a social practice. These competences were focused on perception, performance and creation, suggesting also different possibilities to relate music with other arts and with other subject matters. However, in 2011, the ministry revoked this document, explaining that education should be focused on knowledge content and measurable goals, and not on key competences. The ministry of education argued that it was their intention to create a curriculum based on target goals, but the truth is that, these goals were not defined to music education. Instead, and at that time, the government proposed again the old syllabus from 1989 that is nowadays completely out of date.

Fig 1: Spiral/Square for developing musical concepts

Towards the future

Based on a totally different understanding of the meaning of Education in relation to the previous government, and on the “The Future of Education and Skills 2030”, in March 2016 the Minister of Education invited a number of Portuguese personalities to join a working group whose main goal was to create a document that outlined a "profile of the 21st century student in the end of compulsory education”. Manuela Encarnação, the president of APEM, was one of the persons invited to join this group, which sought to develop a humanist profile, centered on the development of each student as a personal and social human being, an autonomous citizen with initiative, who is responsible, creative and with the capacity and will to learn throughout life. The group, coordinated by Guilherme d’Oliveira Martins, started its activity in June 2016, having completed the document in February 2017, the month in which the document was disclosed for public consultation. After the analysis of the public contributions, the working group met to write the final draft of the document that meanwhile has been approved and published by the Ministry of Education.

As a result of this work, in October 2016, the Secretary of State for Education, João Costa, asked the Portuguese teacher’s professional associations to participate in the process of defining a set of "essential learnings" in each curricular area, within a perspective of horizontal and vertical curricular articulation. This request was justified by the need to focus on the capital contents of each subject, to give more time to deepen each topic within each subject matter, develop a project based approach to the curriculum and interdisciplinary work, to promote greater student interaction, and to make teaching and learning processes more effective. APEM was part of these invited associations and accepted the challenge with enthusiasm. A working group was created that counted on with the APEM Board of Directors, and the Program of Aesthetic and Artistic Education of the Ministry of Education; the work was carried out jointly with other artistic areas to create “common learning organisers for artistic education”, that could be the base for the definition of the essential learning experiences within each artistic discipline. In what concerns music education, when this task was completed the document was analysed by a group of experts invited by APEM (researchers, specialised music teachers and primary teachers). The final version of the document has already been sent to the Ministry of Education and will be disclosed in March for public discussion.

APEM considers these developments as a very important step towards a practice that might ensure that all children and youth have access to music in schools. However APEM is also aware that a lot still remains to be done, and will continue to defend and act to ensure that music exists in its own right for all children and young people who attend the Portuguese public schools in all education cycles.

References

Boal Palheiros, G. & Encarnação, M. (2008). Music education as extra-curricular activity in Portuguese primary schools. In G. Mota & S. Malbrán (Eds.).Proceedings of the XXII ISME International Seminar on Research in Music Education. Porto, Portugal: ESE/FCT, Julho de 2008. p. 96-104.

Bruner, J. S. (2009). The Process of Education, Revised Edition. Harvard University Press.

Ministério da Educação (2001). Currículo Nacional do Ensino Básico: Competências Essenciais. Ministério da Educação: Lisbota, PT.

Ministry of Education (2007). Education and Trining in Portugal. Ministry of Education Editorial: Lisbon, PT

Mota, G. (2001). Portugal. In D. J. Hargreaves and A. C. North (Eds.). Musical development and learning: The international perspective , London: Continuum, p.151-162.

Mota, G. (2007). A Música no 1o Ciclo do Ensino Básico: contributo para uma reflexão acerca do conceito de enriquecimento curricular. Revista de Educação Musical, (128–129), 16–21.

Mota, G., Costa, J., & Leite, A. (2002). Educação musical em contexto: à procura de uma nova praxis. Journal Music, Psychology And Education, (4), 67- 83. doi:10.26537/rmpe.v0i4.2418